First Impressions: Zombie, by Fela Kuti

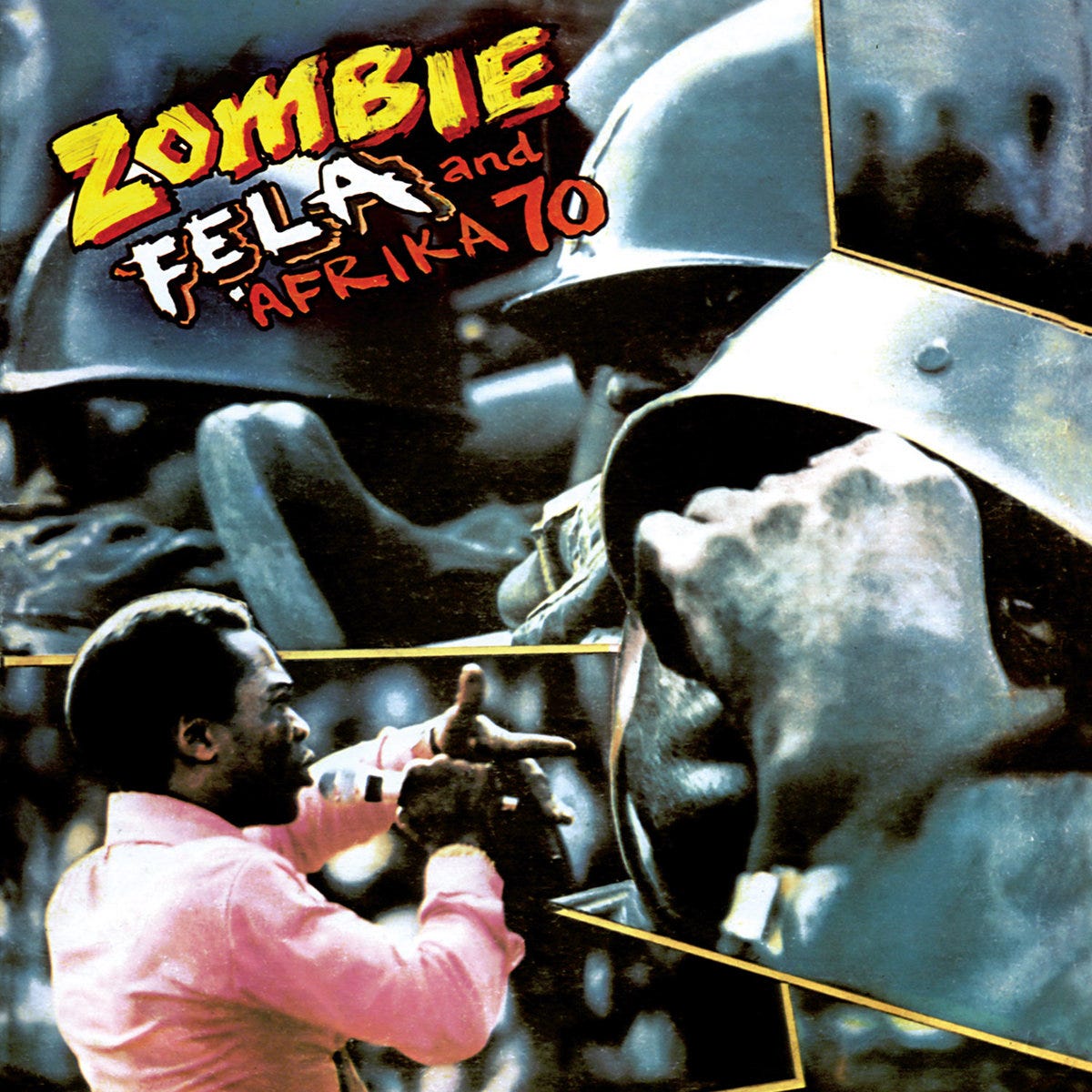

A few thoughts on my first encounter with Zombie, Fela Kuti's 1978 album.

"In January 1984, when I first met Fela, at the Russell Hotel in Bloomsbury, central London, I asked him which musician he most respected. The answer was unexpected. 'Handel. George Frederick Handel.'" (Peter Culshaw)

"Zombie no go turn unless you tell am to turn.

Zombie no go think unless you tell to think."

There's a reason why I tend to shy away from covering artists as popular and well known as Fela Kuti. Simply put, because others can and have done it better than I can ever hope to.

I also spend a lot of my time digging around in more obscure places (that's not a slight on those places), such as Botswana and Malawi. And there's only so much music one can listen to and write about.

But onward we go. This is the first time around for the First Impressions feature. I'm hoping to do more. As the name suggests, I'll look at music - probably an album - by an artist or group I know little or nothing about.

This first installment is a bit of a cheat. I know the song "Zombie," by Fela Kuti. I've listened to it a few times over the years. But I don't know the album (also called Zombie) or much about Kuti, in general.

What little I knew about him were a few stray facts about the harassment visited on him by the Nigerian government. Fela dared to criticize them repeatedly and they did not take it well. The compound where he and those in his circle lived was attacked by the Nigerian military several times in the Seventies and his mother died as a result of one of the attacks.

Rather than back down, Fela amped up his criticisms. Surprisingly, he lived until 1997.

In 2021, Fela was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, along with The Go-Go’s, Jay-Z, Tina Turner, Carole King, Foo Fighters, and Todd Rundgren.

But let's move on and leave the rest of the biographical stuff to those more qualified than I. Start with "The Big Fela," an overview of Fela's life and music published in The Guardian, in 2004.

Trying to make sense of the bewildering number of editions of Zombie reminds me of what a Fela newbie I am. A visit to Discogs had me ready to throw up my hands.

Then I found this summary, "Original LPs have 2 tracks: 'Zombie' and 'Follow Follow' (sometimes 'Mister Follow Follow'). CD reissues add 2 bonus tracks recorded live at the 1978 Berlin Jazz Festival." Which happens to be one of the editions I've been listening to.

"No brains, no job, no sense joro jara jo;

tell am to go kill joro jara jo;

tell am to go quench joro jara jo."

Growing up listening to classic rock and then punk and metal, I became convinced that nothing good could come of music without a distorted guitar or two or three. But of course that's not true and "Zombie" is a great example.

The song opens at a brisk pace, with percussion, bass and guitar. The latter is understated and mostly vamps on a rhythm pattern throughout. It's the horns and the blistering sax that drive things along for more than five minutes before Fela's vocals kick in.

This seems to be the groups's modus operandi, at least on these four tracks. "Zombie" clocks in at a little over twelve minutes and then we're off to "Mister Follow Follow." It almost reaches the thirteen-minute mark.

The pace slows down here, but the intensity level does not. The first time I heard the song, it felt like Fela's vocals snuck up on me just past the seven-minute mark. I could listen to these intros all day long. Aside from the bonus live track here, I've never heard any live Fela. But it's my guess that the intros were even longer when the group was on stage.

The "bonus" tracks are each a couple minutes longer. "Observation Is No Crime" is kind of laconic (in a good way). An almost lyrical sax line stands out in the intro as the band vamps away, more horn blasts driving things along. And again, the vocals kick in around seven minutes.

That track is billed as a live one, but lacks any audience sounds I could hear. Not so with "Mistake," recorded at the Berlin Jazz Festival, in 1978. In Mabinuori Kayode Idowu's notes at the Bandcamp site for the album, it's suggested that at least some of the noise is the audience booing. The vocals come in at about 8:30 and the song clocks out at about a quarter of an hour. And I didn’t hear anything to boo about.

My first impressions, such as they were? Color me impressed. I see more Fela in my future.

My initial experience with “Zombie” was an older guy’s version of the one in the article. In 1980 I was a young classical musician, just starting on a MA in music composition at UC Berkeley. A friend loaned me two African LPs: the original Nigerian pressing of Zombie (with only the title track and “Mr. Follow Follow,” and Ice Cream and Suckers, a compilation of raw South African mpqanga tracks. Both changed my life, and still affect me 45 years later.

Even though I was mired in classical academia, I began obsessively learning African guitar parts from import LPs, Before long I as studying at Cal with C.K. Ladzekpo, the great Ghanian drummer and music scholar. He knew I was a guitarist, and after a while he asked me about trying out with a band he played with — Ashiko, led by Nigerian bandleader and saxophonist O.J. Ekemode, who also performed under his first two names, Orlando Julius. (He had a few hits in Nigeria before coming to the States with Hugh Masakela’s band. Ironically, the forementioned Ice Cream and Suckers compilation includes the TWO songs that Masakela plagiarized and combined into his biggest hit, “Grazin’ in the Grass.”)

Fela wasn’t available on US pressings at the time, except maybe for that Ginger Baker collaboration. I haunted every African record shop I could find, buying those expensive Nigerian imports with their funky covers and sketchy vinyl. I learned a lot of the repertoire, but “Zombie” has always been my favorite. Maybe because it was my first exposure to afrobeat (other than the Talking Heads’s afrobeat-influenced tracks). Or maybe because it’s just so damn good.

At the time, there was an astonishing expat African music scene in Oakland. It included Nigerian and Ghanian musicians who had worked in Africa with major stars like Sunny Ade and Sonny Okusuns. There was Ghanaian percussionist Kwashi “Rocky” Dzidzornu, who had worked in the London session scene for years. You hear him on albums by Nick Drake, Herbie Hancock, Stevie Wonder, Taj Mahal, and most notably, the Rolling Stones. (That’s him playing congas on “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking.”) He also played a bit with Hendrix, including the Woodstock show. And I did a few gigs with Fela’s Tunde Williams, who played trumpet on “Zombie” and many other Fela tracks. In Ashiko I was one of three white musicians alongside a dozen or so West Africans and a couple of African-Americans. We played mostly afrobeat and highlife, with a bit of African reggae. (We did a killer version of Fela’s “Water No Get Enemy.”)

Needless to say, it was an astonishing learning experience. I still marvel at my luck nearly a half-century later.

My role was “tenor guitar,” which referred not to the four-stringed instrument of that name, but rather the electric guitar that played afrobeat’s signature mid-register, staccato single-note lines, like the part you hear at the very beginning of “Zombie,” accompanied by claves. (Or “clips,” as the Nigerians called them.) The two-part figure repeats without variation for the duration of the song. (Of course, there are no alternate chorus or bridge parts because the song has no chorus or bridge.) It required discipline and focus — it was like meditation, decades before I discovered meditation. It was never boring, though — in afrobeat, the tenor guitar, claves, and sometimes other instruments played without variation, while all the other drummers continually varied their parts around our static rhythms. It was a bit like how, when you’re on a merry-go-round, it can feel like the world around you is spinning rather than you.

OJ couldn’t have been cooler. He was so kind and patient with me while I got the grooves under my fingers and in my head. Like I said, I was lucky AF.

I dropped out of UCB PhD program and spent the rest of my life playing guitar in bands — initially African-influenced ones, and then a wider range of styles.

A few years later I was an editor at Guitar Player magazine and a late-blooming session musician. I went on to play with Tom Waits, PJ Harvey, Tracy Chapman, and many other artists. I seldom played in a literally West African style, but those styles informed a huge percentage of what I play to this day — the reliance on crisp, non-distorted sounds … sometimes embracing repetition over variation … and generally, a more adventurous sense of rhythm than most US guitarist bring to the table.

A few years ago I connected with Orlando Julius on Facebook. He was back in Lagos. I had the chance to thank him for all he taught me.

One amusing/irritating detail about “Mr. Follow Follow,” the flip side of “Zombie”: In the mid-’80s George Clinton quoted that fabulous melody in his great track “Nubian Nut,” crediting Kuti as a co-composer. I always compared that to Michael Jackson’s appropriation of Cameroonian Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” on his hit “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’.” Dibango received no credit.

Sadly I’ve never been to Africa and, unlike a few musician friends, I never got a chance to play with Fela drummer Tony Allen. I did a few albums and shows with Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who knew Allen and played with him. (“The nicest man in the world,” Flea said.) Flea told me about his experience going to Lagos and playing a gig at Fela’s club, the Shrine. He said the audience was quite hostile seeing a white American on that storied stage. He told me he spoke directly to the audience, saying something along the lines of “You have your style and I have mine — let’s respect each other.”

ANYWAY … reading your Fela post took me straight back to the shock and awe I felt in 1980 when I met “Zombie” for the first time. Thanks for that.

I was lucky enough to see Fela live, in Los Angeles, in the summer of 1989. I read many years ago that he would perform new material live, but once he recorded a song, he stopped performing it — because it dealt with a particular social issue — and start working on the next thing. My memories of the concert I saw are not that detailed, but I remember what seemed like an extraordinary number of musicians and a whole company of dancers onstage, and the music going on and on like one big two-hour song. (The following year, I got to see King Sunny Ade in New York; he played for **eight** hours, from 8 PM to 4 AM.)